Resilience to extreme heat: what does it mean for Scotland?

Published: 25 July 2022

The extreme heat events we saw in July 2022 won’t be a one-off. It is vital Scotland prepares now for resilience to heat in subsequent years. But what exactly does this mean?

Leslie Mabon

Lecturer in Environmental Systems, The Open University

Heat isn’t something we are used to seeing as a problem in Scotland. In a country where we more readily associate wind, rain and snow with disruption, our media and popular culture have often taken a trivial approach to high temperatures, with images of people gathering in parks and the glorification of a ‘taps aff’ culture. But as the extreme heat events of mid-July showed, even for previously more temperate climates like that of Scotland, heat is becoming an increasingly dangerous and deadly hazard under a changing climate.

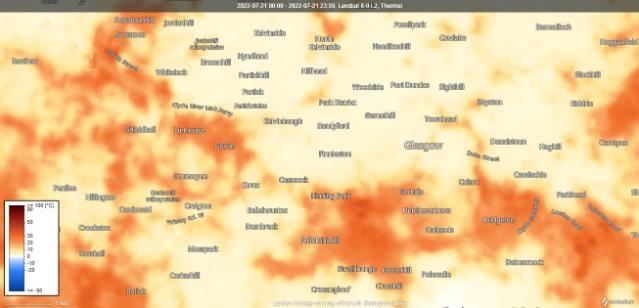

Landsat satellite imagery showing surface temperature variations across Glasgow City Region for 21 July 2022. Note that this image is purely for illustrative purposes to show how temperature can vary across short distances during a day, and is not necessarily indicative of high- or low-risk areas in Glasgow

The temperatures we saw in Scotland in July – and will continue to see year on year as risks from climate change intensify – represent an emerging hazard for Scotland. However, there is a wealth of evidence globally about the dangers of extreme heat, and what can be done in response.

Heat does not affect everyone equally. This is partially due to physical differences. For example, older people, especially those over the age of 70, are at higher risk due to decreased physical ability to regulate temperatures. People with cardiovascular diseases or underlying health conditions may similarly be more susceptible to rising temperatures. And people who work outdoors may have fewer opportunities to shield from the heat. However, social scientists and scholars of resilience have also long argued that societal factors can influence who and where is at risk in hot weather. Those with higher incomes can afford and power cooling technologies like air conditioning. Access to information and communications technology such as smart phones can enable us to check temperatures and get real-time advice on how to stay cool. Cultural factors also come into play. In a seminal study into the 1995 Chicago heatwave, American sociologist Eric Kilinenberg found that neighbourhoods where people were more closely connected and more likely to check in on each other fared better, and suffered fewer deaths during the heatwave.

The built environment also affects the risks people face under extreme heat. ‘Urban heat island’ effects – where high temperatures are magnified by the buildup of concrete and non-reflective surfaces – means towns and cities are generally warmer than their surroundings. Trees, parks and greenery can all help to cool down the surrounding environment in urban areas. Again, though, this has a social and political dimension. There is evidence globally to suggest that less wealthy neighbourhoods may have less availability of green spaces, and can be hotter on warm days. This may be due to ‘green gentrification’, where wealthier residents drive up house prices in areas which have seen investment in urban greening, or due to historical urban planning decisions that have discouraged investment in greening in some parts of cities for reasons of class, race or ethnicity.

What does all of this mean for Scotland, and what can we do about increased instances of extreme heat? Whilst it is helpful to draw on the rich body of evidence that exists globally, ‘what works’ in once place won’t necessarily work elsewhere. A lot of the evidence on extreme heat comes from the North American context or from cities in tropical zone countries, where the physical geography and the social, cultural and political dynamics are very different to Scotland. So it is important that we in Scotland develop our own evidence base of who and where is at greatest heat risk, and why. The foundations for this are already in place. In their Glasgow City Region Climate Adaptation Strategy, Climate Ready Clyde have used remote sensing data to identify places in Glasgow City Region that might be at greatest heat risk, so they can be targeted for support and interventions. Researchers from Glasgow Caledonian University have looked at how the cooling benefits from green spaces are distributed across Glasgow, and found that more deprived areas may receive less of the cooling benefits than their wealthier counterparts. Outside of Glasgow, the University of the Highlands and Islands has been doing work into understanding how the temperature varies across Inverness on hot days. And under a new project funded by the British Academy, myself along with colleagues from the Open University, Climate Ready Clyde and Ming-Chuan University in Taiwan will be working with neighbourhoods in Glasgow and Taipei to understand how residents themselves experience extreme heat and the cooling benefits from green spaces.

The extreme heat events we saw in July 2022 won’t be a one-off. It is vital Scotland prepares now for resilience to heat in subsequent years. From a societal perspective, this means ensuring health and emergency services are ready to respond on hot days, and also that community leaders are trained in knowing who might be at risk and checking in on them regularly during warm periods. Being resilient to heat also means social and behavioural changes, for instance working from home – or taking days off completely – when temperatures are high, and keeping public facilities open as ‘cool-sharing’ spaces. As the evidence base grows of what drives heat risk in Scotland, local governments and resilience partnerships may even be able to engage with communities in high-risk areas to prioritise cooling initiatives such as tree planting and alert systems. As with all hazards, heat is a social and political challenge as well as an environmental one, so Scotland’s heat resilience response needs to address social and physical drivers of extreme heat risk.

Dr Leslie Mabon is a Lecturer in Environmental Systems at the Open University. Leslie’s research focuses on resilience to environmental change, especially in coastal zone areas. Leslie has research experience in his native Scotland, and also in east and south-east Asia – especially Japan and Taiwan. He is currently leading a British Academy-funded project into urban greening for heat-resilient neighbourhoods, and is co-leading an ESRC-funded UK-Taiwan project into climate-resilient neighbourhood. You can read more about his work on his blog resilientcoastal.zone, or on Twitter @ljmabon.

First published: 25 July 2022

<< Blog